In the previous posting I discussed the Daoku Wheel of the Year, the daoku calendar that is in essence remarkably close to the old calendar not only of the hokku writers of old Japan but also that of the old Chinese poets, with only slight variation, though of course the names of the chief seasonal points differ.

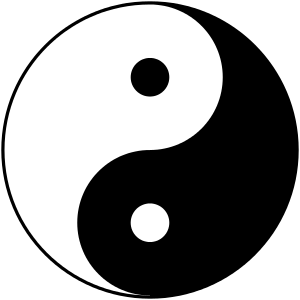

Having read that posting, you will have noticed that we can also describe the seasons in the following way, as they relate to the two opposite but complementary forces of the universe — Yin and Yang:

Spring: Yang grows as Yin declines.

Summer: Yang grows until it reaches its maximum at Midsummer’s Day, then gradually declines as Yin begins to increase.

Autumn/Fall: Yang declines even more as Yin continues to increase.

Winter: Yin increases until it reaches its maximum at Yule, the Winter Solstice, then gradually declines as Yang begins to increase.

For practical purposes then, we can describe the seasons like this, according to their predominant energy:

Spring: Growing Yang

Summer: Maximum Yang

Autumn: Increasing Yin

Winter: Maximum Yin

You will recall that Yang is the energy of warmth and activity; Yin is the energy of cold and passivity. So we think of spring and summer as being increasingly warm and filled with activity in Nature, while we think of autumn and winter as being increasingly cold and a time of growing inactivity in Nature.

Daoku is about Nature and the place of humans within and as a part of Nature, set in the context of the seasons. Every verse is set in a particular season, because that season not only connects us with the natural world, but it also provides the environment — the context — in which a daoku event happens. That means the seasons are an integral part of daoku.

In old Japanese hokku the seasonal connection was made in each verse by using a season word that — by accepted convention — indicated a particular season. Anyone wanting to write or understand hokku had to learn those season words in order to know (except when obvious) the season in which each verse was set. Over time the number of such words greatly increased, until near the end of the old hokku period near the beginning of the 20th century, it required years for one to learn the season words and how to use them properly, a growing complexity that was not really in keeping with natural simplicity.

The old season words were also based on a particular and rather limited climatic region of Japan, as well as upon plants, animals, birds and fish within that particular region. Can you imagine how complex and difficult it would be if we expanded that region worldwide and included not only all climatic regions but all natural life?

That is why in modern English-language daoku, we take away the complexity and return to simplicity by using only four seasonal markers — the four seasons. Every daoku, when written, should be marked with the season in which it is written. That way, when it is shared with others the season goes with the daoku. And if a group of such verses are gathered into a collection or anthology, all the verses can be easily classified under their respective seasons. This takes a huge burden away from learning daoku while still keeping the essential connection to the seasons.

So now you know a lot about the seasons and the cyclic changes in Yang and Yin energy through the year.

That brings us to the important matter of internal reflection.

As you saw in the previous posting, the changes in the seasons correspond also to these changes in time and in human life. We say they are “reflected” in these other things. For example, here are some general reflections:

Spring: Beginnings (Growing Yang)

In human life: birth, childhood, youth

In the day: dawn and morning

In plant life: sprouting, growing, blossoming

Summer: Maturing (Yang reaches its maximum)

In human life: adulthood, middle age

In the day: mid-day, noon

In plant life: maturing, fruiting

Autumn: Aging (Yang weakens as Yin increases)

In human life: “Getting old,” roughly the years from 40 onward

In the day: late afternoon to dusk

In plant life: plants “gone to seed,” leaves withering and falling

Winter: Endings (Yin reaches its maximum)

In human life: Very old age and death

In the day: after sunset to deep night

In plant life: death and dormancy.

These are just some of the most obvious correspondences/reflections.

So how do such reflections manifest in daoku? By putting together things that are the same in character. This is called harmony of similarity.

Here is a very obvious example of putting things together that reflect one another:

An old man walking in the autumn amid falling leaves.

As you can easily see, everything in this verse has the character of weakening Yang and increasing Yin. The year is old (autumn), the man is old, and the leaves are old. That is why this combination gives us a feeling of harmony, the feeling that these things just “go together.” That is harmony of similarity, and it is achieved by using, in this case, things that reflect the nature of autumn, Yin things.

Similarly, look at this assemblage:

A child picking snowdrops amid the melting snow.

That is very obviously a collection of “beginnings” The child is young (beginning life), the snowdrops have just sprouted into bloom and are “new,” and the melting snow shows us the increasing of the Yang (warm) energy. So it automatically makes us feel the sense of newness and fresh beginnings of the early spring.

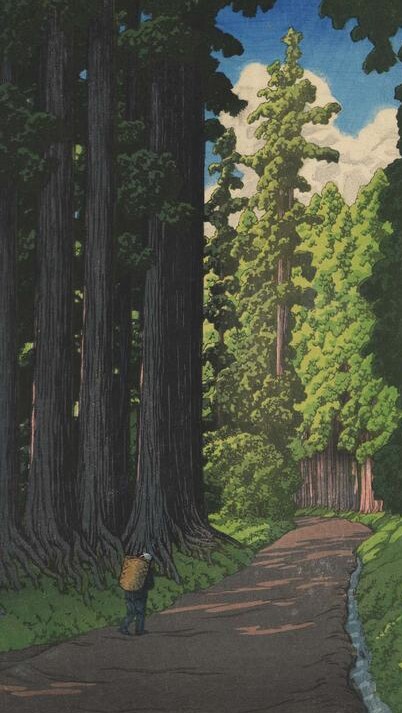

Now, keeping in mind the list of Yin-Yang correspondences that you saw in the previous message, take a look at this verse by Bashō:

(Autumn)

On the withered branch,

A crow has perched:

The autumn evening.

You should easily be able to see the internal reflections. Just in case you have overlooked one of the elements, I will remind you that bright things are Yang, dark things are Yin. Do you see now how each element in the verse reflects the others?

Here is how it works:

Heading: The seasonal marker “Autumn” (It is not really needed to indicate the season in this verse, but it is in many others, so we always include it for ease of classification)

First line:

On the withered branch

A withered branch is an old branch, so that gives us the sense of age, which is Yin.

Second line:

A crow has perched:

The crow is, of course, black; and darkness is a Yin element. Also, the crow has settled into inactivity, which is also Yin.

Third line:

The autumn evening.

Autumn is the time of increasing Yin; evening is also a Yin time in the day.

So everything in this verse is Yin, everything has to do with aging, and there is a correspondence between the darkness of the crow and the gathering darkness of evening, as well as the reflection of the withering of nature in autumn with the withered branch on which the crow has perched.

It is very important to see that these corresponding elements reflect one another. The Yin we see in one, we also see manifested in some way in the others. Do not mistake this for symbolism. Each element is fully itself, while also being fully in harmony with the others and with the autumn season.

Let’s look at another verse, this time by Issa. Here is R. H. Blyth’s translation. I have added the seasonal marker:

(Autumn)

Visiting the graves;

The old dog

Leads the way.

The seasonal marker is essential to understanding here, because otherwise we might think it to be Memorial Day, a spring holiday. But knowing it is an autumn verse makes all the difference because of internal reflection:

First line:

Visiting the graves;

Graves, of course, we associate with the passage of life and with and death, and both aging and death are Yin elements.

Second and third lines:

The old dog

Leads the way.

It makes all the difference that the dog is old. His age is in harmony with the season (Autumn – increasing Yin), and with the graves (death = maximum Yin). So both are Yin subjects, set in a season of increasing yin, a season of withering and dying. We can see the dog, showing his age in the slow pace of his walk, taking the lead on a path he has gone down many times.

Just for contrast, let’s look at what would happen if we changed the Yin dog to something freshly Yang:

Visiting the graves;

The awkward toddler

Leads the way.

That gives us a completely different feeling. It lacks the obvious harmony of Issa’s verse, though there is a place for using contrasting elements, as we shall find.

Now you know about internal reflection in daoku as well as harmony of similarity. Now we come to a different (but related) technique, harmony of contrast. It too is based upon Yin and Yang, but it creates a different, yet still harmonious effect by using “opposite” elements.

Again if all of this seems a little difficult, it is only because it is likely new to you. Once you are accustomed to this way of thinking you will easily and naturally see such correspondences. But to do this well, you must know about Yin and Yang, so if those are not clear in your mind, just review the previous posting with its list of characteristics of Yin and Yang.

You will recall that harmony of similarity is the combining of things with similar characteristics, for example an assemblage of things that are aging or old, or things that are Yin in nature or things that are Yang in nature.

When we combine things with similar characteristics (such as the billowing sail on a boat and billowing clouds) or energies (such as an old woman and autumn — both increasing Yin), that creates a very harmonious feeling.

Harmony of contrast is the use of elements that are felt to be contrasting or opposite in their characteristics (such as an old woman looking at apple blossoms in spring) or energies (such as stepping into a cool stream (Yin) — on a hot day (Yang).

As you might imagine, the combining of contrasting things can be particularly effective in the two seasons when energies reach their maximum — Yang in summer and Yin in winter. But it can also be used in the two seasons when Yang is increasing as Yin declines (spring) and when Yang is declining and Yin is increasing (autumn).

The moon is felt to be a silent, passive and tranquil element. The pecking of a bird, by contrast, is active and jerky. Though we feel these things to be contrasting in character, we can combine them, as did Zuiryu in this verse (I translate a bit loosely here):

(Autumn)

A water bird

Pecking and breaking it —

The moon on the water.

Here is an example of a verse using contrary actions, this time by Ryuho:

(Autumn)

Scooping up

and spilling the moon;

The washbasin.

Of course it is the moon seen at night in the water of the basin.

One can also mix contrasting and similar things; for example, here is a verse by the woman Sogetsu-ni:

(Autumn)

After the dance,

The wind in the pines,

The crying of insects.

We see harmony of contrast between the boisterous music and activity of the dance (now ended) and the peaceful, quiet sounds of the wind in the pines and the crying insects. But there is also similarity between the “natural” sound of the wind and that of the insect cries.

Here is a slight variation on an old verse by Issa in which we again see harmony of similarity:

(Autumn)

Withered pampas grass;

Wisps of my hair

Quiver with it.

There is a mild similarity between hair and the feathery plumes of pampas grass trembling in the (implied) wind, but if we think of the writer as OLD, the effect becomes even stronger — the grey, long and unkempt wisps of an old man’s hair trembling in the same autumn wind that blows the white, withered pampas grass. But if the hair trembling in the autumn wind is that of a YOUNG man, then the feeling of the verse becomes quite different, not nearly so harmonious with the season.

In using harmony of contrast, you can even use something that is there combined with something that is not, as in this verse by Fugyoku:

(Autumn)

The bright moon;

No dark place

To dump the ashes.

The reason it works is that the absence of something can often be just as strong, or sometimes even stronger, than something that is present. Imagine, for example, seeing the empty and silent rocker in which a beloved grandmother used to sit. That is a very meaningful absence.

Long ago I wrote a somewhat similar verse:

(Autumn)

No moon;

Everywhere in the forest —

Deer eyes.

For those of you who do not know, on a dark night any light carried reflects off the eyes of deer, and all one sees are ghostly eyes in the darkness.

What these techniques teach us, aside from being frequently useful in composition, is to pay great attention to the interrelationships among the elements you put into a daoku. You should always remember that a good verse is not just an assemblage of random elements. It is not just picking anything you see and writing about it in three lines. It is noticing events in which we FEEL the relationship among the elements and their relationship with the season, whether that relationship is one of similarity or contrast, or even a mixture of the two. That is what gives a daoku depth and significance.

Keep in mind too, that the feeling of an element changes with the season. Spring rain is very different in feeling from summer rain; and autumn rain has its own feeling, as does winter rain, which is quite different than spring rain. That is why we should keep in mind that underlying the obvious subject of a daoku is also the more encompassing subject — the season in which the verse is written.

All daoku, you will remember, should be written in the appropriate season. We do not write winter daoku in summer or fall daoku in spring. And we ordinarily also read daoku in the appropriate season. We do not read summer daoku in winter or spring daoku in autumn. This practice keeps us in harmony with the seasons, and avoids creating the sense of inappropriateness we feel when seeing artificially grown spring flowers in an autumn bouquet, or when dried autumn plants and seed pods are used in a spring bouquet. The exception to that is — as here — when we are studying daoku and its principles. Then we may use examples out of season.

David